Welcome to the Art&Seek Artist Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the personal journey of a different North Texas creative. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will eventually paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists we’ve profiled.

Enjoy, and let us know what you think in the comments section below.

Adrian Hall was fired in 1989 after running the Dallas Theater Center for six years. He was fired for essentially being ‘difficult’ — being late with a season of plays to announce, acting high-handed with both staff and board.

“I was impatient, yes,” Hall admits today. He was already 55 when he was hired, he says, and it had taken him 30 years to establish the Trinity Repertory Company in Providence, Rhode Island, create its celebrated acting ensemble and win a 1981 Tony Award for the effort. And now he was expected to do it all over again in Dallas. So Hall focused on getting things done, not spending time on anything that didn’t fit his goal of reinventing the DTC.

As former ‘Dallas Morning News’ theater critic Jeremy Gerard has put it, “I don’t think the Theater Center had a clue what it was getting into when it signed Adrian on.” The DTC dumped its children’s company, for example — generating some ill will and setting director Robyn Flatt on the path to creating the nationally recognized Dallas Children’s Theater.

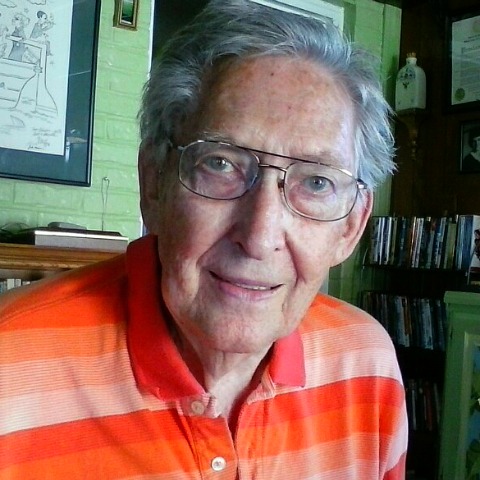

Adrian Hall in 1987 in the Arts District Theater. Photo: KERA

But when it came in 1989, Hall’s dismissal wasn’t a complete surprise. The board had already asked him to resign and he’d refused — he’d just bought a house in Dallas. Besides, Hall was already a legend in theater circles for effectively ‘firing’ his own board at Trinity in 1976. They announced his dismissal, but he and his actors rounded up a new set of board members. In Dallas, Hall knew some members were unhappy with him, but who would seriously move against a director who’d once replaced his entire board?

Yet there they were — the DTC board reps came to Hall’s new Swiss Avenue-area home and fired him, with his furniture still in boxes out on the lawn, just arrived from Rhode Island.

It was a shock but hardly a setback. Hall was soon in demand as a freelance director, working in San Diego, Seattle, Los Angeles. He was hired so often in New York, by 2012, he’d even leased an apartment there.

But then Hall learned something he’d been fearing for some time. He’d been having problems: dropping things, forgetting things. He had been diagnosed with a ‘mild cognitive impairment’ (MCI, now recognized as a possible indicator of future dementia).

But his symptoms were getting worse.

“Finally,” Hall says, “the doctor said, it is Alzheimer’s.”

So he gave up the New York apartment and returned to Texas. “And as the Alzheimer’s really closed in on me,” Hall says, “I just closed the world off as much as I could.”

The world Adrian Hall lives in now, with the help of a caretaker, is Van, Texas. It’s the tiny town 80 miles east of Dallas where Hall grew up on a farm during the Depression. Since coming back here, he’s sold his family’s big, old home and lives nearby in a suburban-style brick house. It’s packed with theater memorabilia. The walls are covered with posters and photos.

“And I guess that must be John Morrison,” Hall says, peering at a photo of a former Theater Center company member. “And that’s Nance,” he says, pointing near Morrison to Nance Williamson, another DTC ensemble actor.” So I think this was in Seattle.”

In his home, the shelves and tables are thick with awards and books and playscripts: Hall is a theater legend. He’s the only person to run two major theaters simultaneously, the Theater Center and Trinity Repertory, which he founded in 1964. (For context: The Dallas Theater Center itself was founded only three years earlier. So Hall goes back that far in the resident theater movement.)

‘The Tempest,’ directed by Adrian Hall, Dallas Theater Center, 1987

More than that, Hall became known for his distinctive, epic style. As much as he was celebrated for working with new American plays and establishing resident acting companies, Hall had a style that was visceral, exposed and starkly flamboyant (partly influenced by Jerzy Grotowski’s famous theories about “poor theater”).

It was all about the direct engagement of actor and audience. Hall hated faking things on stage — he showed you the tricks, the machinery, and made that theatrical. If wind was needed, the giant fan would be in full view, roaring away onstage. When performers flew overhead as ghosts or gods, you’d see the harnesses and pulleys being operated. Smoke machines would be out in the open, cranking out clouds in front of you.

And onstage, actors wouldn’t always speak to each other, pretending the audience wasn’t there. In what’s called ‘direct address,’ they’d frequently simply stand together and speak to the audience. New or radical? The entire technique started with the Greeks, Hall pointed out happily.

All of that is partly why Hall turned to adapting classic American novels such as Herman Melville’s ‘Billy Budd’ and Edith Wharton’s “Ethan Frome.” He could sidestep conventional American stage realism. The novels gave him scope and a cast of characters he could unleash his actors on. They gave him a way to respond to the Grotowskis, the Peter Brooks, the Europeans — directors who developed their own radical thinking in the ’60s and ’70s (often independently).

And Hall could be part-playwright as well, working on themes close to home. With Robert Penn Warren’s ‘All the King’s Men’ — first staged at the Theater Center in 1986 and then at Trinity Rep and Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. — Hall added Randy Newman’s ironic, flavorful songs about Louisiana, including “Louisiana 1927,” about the great flood that nearly wiped out the state, and “The Kingfish,” a song about Governor Huey Long, the inspiration for Warren’s novel. In the end, Hall created what amounted to a dark, musical reflection on American politics, despotism, racism and the South. What Steppenwolf later did on Broadway with ‘The Grapes of Wrath,’ Hall first did with ‘All the King’s Men.’

“The Americana material was so rich,” he says, “and so much what I really wanted out of the theater, to help create an American theater.”

Hall is 88. He stumbles over names and dates. Conversation, he admits, is more difficult these days. “I know it doesn’t sound like it because I ramble on so, but that’s why I don’t like much contact with the outside world.” Remembering all those names of the actors in the photos? On the backs of the pictures, he’s carefully written the names, the titles of shows, dates and where they were staged.

But as he says, he knows there will come a time when even that won’t help. The names and faces won’t mean much to him anymore.

Even so, these days, if Hall gets on to a favorite topic – like how the theater mustn’t be crippled by corporate demands — he still can preach like a young firebrand quoting the Scriptures.

“The theater is thousands of years old,” Hall declares. “And it has always been man’s attempt to tell the stories that mean something to the people there. And most of all, it’s alive! It’s right in front of them.”

Dallas Theater Center company member Linda Gehringer and Joseph Hindy in ‘Les Liaisons Dangereuses,’ directed by Adrian Hall, Dallas Theater Center, 1988

It’s one reason many actors have been devoted to Hall: He believes fully in the redemptive, transformative power of theater, the human need for it. The other reason they love him: He created true acting ensembles, fought for keeping his actors hired and paid, believed in acting as a worthy profession, a full-time art, the art at the center of any theater. He wanted to give performers the chance to live out here on the prairie — and not have to move to New York or LA. Or have to quit theater entirely for office jobs.

At the Theater Center, Hall established its first professional acting company with 15 members (the current DTC acting company was created seven years ago with nine members. Today it has ten — give or take a few who’ve been leaving and may be replaced). In 1984, Hall took a huge risk and built the Arts District Theater, a corrugated-steel warehouse where the Winspear Opera House now stands.

It was raw, flexible and a delight for inventive artists — like ‘Saturday Night Live’ set designer Eugene Lee, who devised the entire space himself. Hall needed that kind of wide-open facility to stage the work he was doing; it simply wouldn’t fit in the Kalita Humphreys Theater. But even Hall calls the Arts District Theater the ‘tin barn.’ It wasn’t a glamorous, Dallas-style, velvet-seat affair; local theatergoers were assured it was really only temporary. But it lasted for more than two decades. When it went up, the Arts District itself was just starting — the Meyerson Symphony Center itself wouldn’t open for another five years. But Hall was going to make sure theater was in the heart of it.

“Where the people are,” he says, “is where the theater’s got be.” In effect, we owe the Wyly Theatre to Hall’s initial push downtown, to get out of the Kalita Humphreys, to get a toehold in the district.

Today, Hall is one of our last, living connections to the off-Broadway movement of the 1950s and to the history of the American resident theater movement. He is a rarity. He knew Tennessee Williams and Judith Malina and Julian Beck, who founded the Living Theatre in New York in 1947. He knew Margo Jones, the theater pioneer who established one of the country’s first professional regional theaters in Dallas in 1947.

But now we may be losing some of that history. Hall is well aware of what his deteriorating mental condition means. His mother died of Alzheimer’s.

She lived to be 92, he says, and in the last years of her life, “she really recognized nobody, she recognized me but not the people who attended her. They dressed her, diapered her. And that’s not something that I … ” his voice trails off.

“I hope,” he says quietly, “that I won’t live that long.”

Hall sees one positive aspect to his Alzheimer’s. It’s caused him to assemble the archive that now surrounds him at home. The word ‘legend’ comes from the Latin for ‘to read,’ but it also means ‘to select, to gather together.’ Hall has been gathering this rich chronology, piecing together the meanings and connections in his life and career.

“So that’s what I have been doing,” he says. “I live in a world where I am constantly with my past.”

Growing up in small-town Texas, you were drawn to performing at an early age, but when did you see yourself as a director, a professional artistic director?

I grew up in an environment where the hope of my heart had something to do with surprising and confronting whoever it was – the children in the neighborhood, my family — with what I could tell them. I realized the power of the magic of drawing people into this unknown thing — this story – which doesn’t really come alive until it meets its audience.

And again and again, I guess I happened to be in the right place at the right time. That was true when I went to the Army [during the Korean War, he started a touring ensemble in Germany]. It was true when I went to New York for the first time [in 1955], and I went there to find more theater people like me. And it just happened to be the beginning of the off-Broadway movement – a daring, wonderful time – and it brought me into contact with the great people of that period, people like Stella Holt [a leading off-Broadway producer], Tennessee [Williams], the Living Theater, Jose Quintero [co-founder of the Circle in the Square]. And I directed shows then, I just soaked it up like a sponge, when all those people were fighting against the notion that theater could only happen in America in a money-making environment.

But when you established the Trinity Rep in Providence in 1964, was that when you first lead a theater, when you first became an artistic director?

No, in truth, I had led a company before. A group of us went to upstate New York, in Phoenicia, just outside Woodstock. It was Katherine Helmond and Howard London, and we started our own company there. It was called the Phoenicia Playhouse, and it lasted three years [from 1957 to 1959].

Has there been anything you felt you had to give up to pursue your career in theater?

My homosexuality played a big part in my life and career – knowing that I could not always take the path that was in front of me. My mother and father wanted me to marry and have children, and I never really thought that that would be a sacrifice to do that. I thought it would probably come some day.

But the people I sought were people like myself. And very early on, I realized I couldn’t take advantage of a woman, a girl, because she had money and she could help me. I just gave that up. And that meant there was no way for me to please my mother in that way.

So your sexuality was connected to your decision to pursue your art? They both meant ‘taking the path not in front of you’?

Yes. It was connected to my art and my life.

Have you ever been satisfied with your art?

There is great pleasure when that moment happens – the cherry on the sundae – when you confront the audience and they reward you with great applause and reaction, and people say, ‘You’ve changed my life.’ There is satisfaction then.

But if you mean, was there ever a moment that I said, ‘I’ve done it, I’ve made it perfect’? Then no, there never was such a moment. The process, the doing of it is important. But the magic doesn’t happen until it finds its audience. I suppose it’s persuasion, in a way. It’s surprising them [the audience]. It’s getting them to enter an experience they’ve never had, never felt before, or entertain an idea that’s always been closed to them. Many people have their spirituality, that catharsis, through art, not religion. That’s what it is.

Interview questions and answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

COMMENTS