Welcome to the Art&Seek Artist Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we explore the personal journey of a different North Texas creative. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will eventually paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists we’ve profiled.

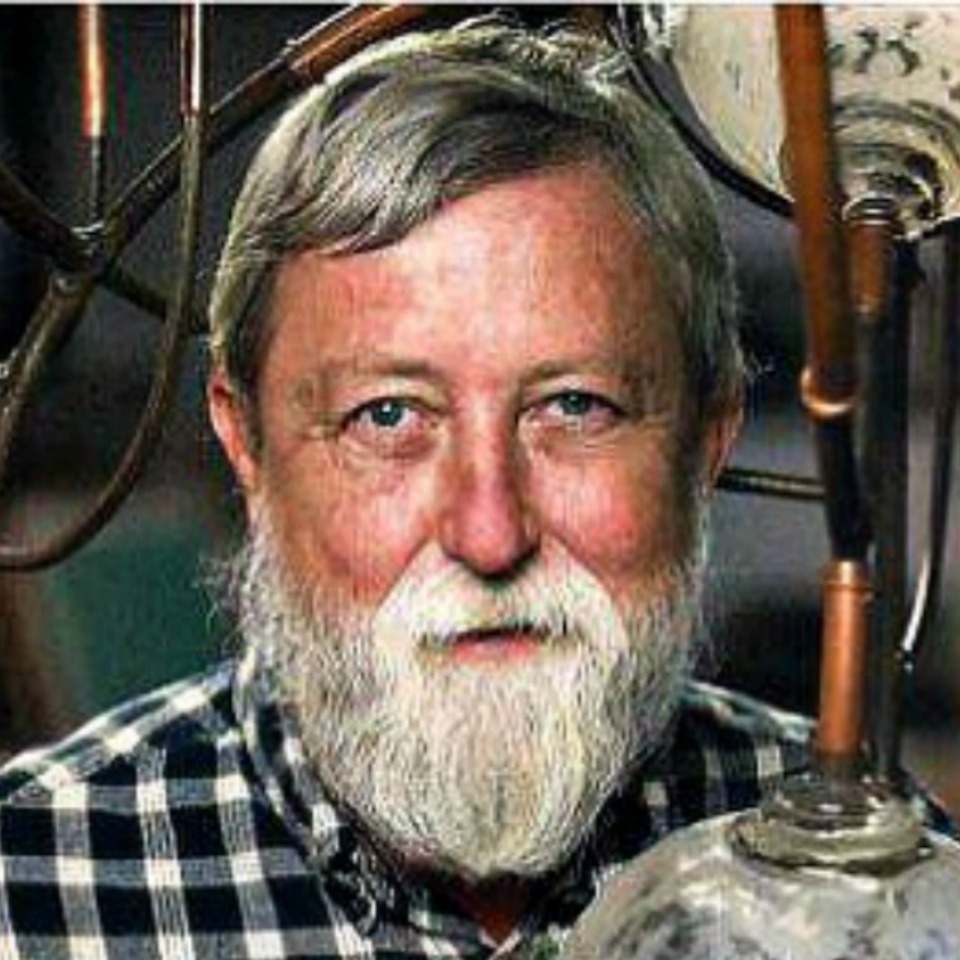

Every morning, Jim Bowman wakes up in his home in Dallas’ Cedars neighborhood, saunters next door to his studio and starts to work.

“I get in the habit of getting up early,” says Bowman. “Just to beat the heat.”

That’s because he works with a furnace blowing more than 2000-degree heat.

Some mornings – particularly in the summer – he wakes up as early as 5:30 to prepare the equipment in his workshop so things are ready to go when his assistant arrives.

Bowman has worked with glass – stained glass, blown glass, fused glass – for around thirty years. But he says he fell in love with the medium instantly: “From the very beginning, when I started getting involved in glass, I was fascinated by the material. And you can never finish exploring the possibilities.”

Inside his studio is every glass style imaginable. Drinking glasses, vases, Christmas ornaments, plates, bowls, wall-mounted sculptures, pieces that hang from the ceiling, even a few paperweights.

Patricia Meadows, the founder of Art Connections, an art consulting business that specializes in corporate and private collections, say Bowman’s work is special.

“Yes, Jim does create works like chandeliers and wall art,” says Meadows. “But he is very accomplished as an artist using glass to create contemporary sculptures.”

Meadows says Bowman has a great reputation. Not many glass artists are known in Texas, but Bowman’s name rings. She recalled a recent time when a Dale Chihuly exhibition was coming to Dallas, and she wanted to put together a showcase of important glassblowers in Texas. Who’d she call? Jim Bowman.

“All of the artists could have done glass rondelles, which is what Chihuly is known for,” says Meadows. “But they decided to show their contemporary work. And Jim’s was just beautiful.”

When I visited Bowman’s studio, he was working on vases with his apprentice Blake Boettcher. Their work process was like a dance. With safety sunglasses on and a handkerchief wrapped around his head to stop the sweat from getting into his eyes, Bowman would pull his blowpipe out of the glowing-hot furnace. Immediately, Boettcher would shut the doors. Bowman would do a sort of shimmy and sidestep to get the pipe and himself in the right position for shaping the piece. And Boettcher would ready himself to blow into the pipe.

As Bowman spun the pipe and shaped the glass, Boettcher would blow into it and the glass would slowly expand. As the glass grew, it began to cool and show its real color. No longer a fiery red but more yellowish-green. That meant it was time to reheat, so the pair would either throw it back into the furnace or use torches to make the glass malleable once again. Glass — this normally sharp, brittle substance — was soft and they pulled and shaped it like saltwater taffy.

Dallas artist Rick Maxwell has seen this glass-blowing ballet himself. He’s amazed by Bowman’s work ethic.

“Jim is the sort of guy that would do anything to help you get your work done,” says Maxwell, “which is hard to find in this profession. And I really learned about his work ethic and generosity when I saw what he did to help the University of Texas-Arlington create their glass program.”

About 15 years ago, Bowman had young people apprenticing under him. But he felt there should be be a school for folks to get the training they needed.

“There’s not a whole lot of people,” says Bowman. “I can count on practically one hand the number of people that are doing glass art with the furnaces and the glass blowing the way we have it here.”

Now UT-Arlington students can get training at the university — and then come to Bowman better prepared. But Bowman is not just a fixture in the glass-blowing community, he’s appreciated in his own neighborhood.

Bowman and his wife Mary Lynn Bowman moved their studios to the Cedars in 2001. At the time, the Cedars were pretty sketchy.

Bowman says you could look up the hill any time of the day and see drug dealers or prostitutes. Rick Maxwell, who moved into the area shortly after Bowman, agrees.

“It was pretty rough back then,” says Maxwell. “We were pretty much counting on being robbed like every night. But there were a lot of possibilities on Griffin Street and having Jim around made things a bit easier.”

The two moved into different properties, but neither place was in great shape when they moved in.

“It was all falling down,” says Bowman. “Everybody thought it should be torn down. But we got in here and got it all fixed up.”

Fixed up as a studio, that is. The Bowmans used to work in the Cedars while living in a historic home in Munger Place in East Dallas. But then the recession came and everything changed.

“We were making a living doing commission work and, you know, things were great back then,” says Bowman. But when the recession hit, “that stuff dried up and we ended up having to sell our house.”

So the Cedars — the tough, industrial neighborhood that was perfect for a workshop — also became their home. Now, other artists have studios on their large property. And they drop by whenever they need a hand or a bit of advice.

So do other neighbors. The Bowmans have a popular, open-studio tour each year, which began before the neighborhood started being developed and gentrified.

“The other artists in the neighborhood, I think they were impressed,” says Bowman. “They didn’t really think that many people would actually come over here.”

But people did. And the following year, the Cedars Neighborhood Association decided there should be an art walk. So other artists in the neighborhood decided to open their doors as well.

At age 65, Jim Bowman talks about losing the athleticism it takes to continue creating large works. And he wonders how much longer he’ll be at it.

“As I’m getting older, it’s getting to be where I blow glass for, like, a couple hours,” says Bowman, “and I start getting these aches and pains I didn’t used to get when I was, you know, in my thirties and forties.”

But he’s not looking to walk away from the craft just yet. He’s finally got the Bowman Glass studio set up to continue creating artworks. Instead, Bowman’s got his eye open for an artist he can share the space with.

And possibly even collaborate with. Because he’s got a whole lot of art left to share.

How has working in North Texas impacted your art?

Well, first off, I feel like there’s a really strong, cohesive artist community in North Texas, and I feel lucky to be able to be in a community that has a good art presence and the support I get there. I feel like especially the Cedars — I feel very fortunate to be in this neighborhood because, right now, it’s kind of exciting because it’s got this buzz. It’s like the latest cool place for artists to be, so there’s a really strong community right here. We have a real tight group of artists where everybody knows everybody.

I could also say that being in North Texas and in the medium that I chose to work in – glass blowing – there’s not a whole lot of people. I can count on practically one hand, actually I might have to use my second hand a little, to count the number of people that are doing glass art with the furnaces and the glass blowing. So it’s a small community of glass blowers here. Not that blowing is the only way to make art with glass. But it makes it a small community.

There is a glass program at UTA, which I was involved in starting back about 15 to 18 years ago. I spent a couple years out there helping to set that up. It’s now run by a very nice guy, Justin Ginsberg. And that probably impacts my world here. It’s kind of grown and is growing the interest here in what I do.

Normally, I ask artists if they’ve been able to quit their day job to pursue their craft. But you’ve been doing this for nearly 40 years. So why don’t you tell me when you were able to take on glass art full time?

To tell you the truth, I only ever had a day job once in my life. I think I was a teenager still and I got a job at a cement factory. I was sweeping floors. There’s a lot of dust in a cement factory. So basically you start on one end and you sweep and sweep and sweep and by time you get to the end, you go back and start again. That cured me of day jobs.

Other than that, when I was in grad school, I did have to work, but I worked in some glass shops in the San Francisco Bay Area. There’s a lot of glass artists there, and I found work at several different glass shops when I was in grad school. But ever since I got out of grad school, my wife Mary Lynn and I have always supported ourselves with our artwork.

You and your wife are partners. You also live right next to your workshop. That means you’re pretty much surrounded by work. So how do you maintain balance in your life?

That’s a very good question. Because it’s tough. It’s probably harder on my wife than it is on me. It can feel like we’re stuck in this little bubble of this art world. Living so close to the studio, it can feel like you can never get away from it. I can’t say it’s easy, but we have a good relationship and I would have to hand it to Mary Lynn for sticking with me after all these years. And for having faith because I think as an artist making a living with no day job, nothing to fall back on, there are times where you’re basically living on faith. But keeping that faith can be hard.

With the shop nearby, do you ever get to just take a break?

We do take breaks from time to time. Our favorite place to get away to is our property in North Carolina, near Asheville. When we’re here in our studio in Dallas, I am basically working seven days week. And when you think of something in the middle of the night, you’ve got to get up and do something about it. It’s just so easy to do because we’re right here. But when we do get away, I’ll just collapse and do nothing for a week, two weeks, three, as long as we can manage to get away. I just think that is necessary. I think everybody needs a break once in a while. You have to create that space in time and find a way to take a break and sort of recharge and heal your body and your mind from constant work and thinking.

When did you begin to call yourself an artist?

I felt like I was always an artist. From the time I was a little kid, I thought I was an artist. I just never gave up on it. My parents were the type that expected their kids to go to college, which they all did, and there was never any question in my mind what my major was going to be when I went to college. I was going to study art.

I don’t know if I ever called myself an artist until I got my training and got out of school. I guess I could’ve called myself an artist, but still those first few years out of school are tough when you’ve got a degree in something that doesn’t make you employable. You basically have to create your own situation. I guess after I had been out of art school for a few years and I had gotten jobs all around – I worked at the University of Texas washing lab equipment and I worked at a YMCA managing community gardens – I got a job doing glass work. My job title actually was ‘artist’ and from then on I really considered myself an artist. I probably still have to ask myself questions every day. ‘Who am I?’ ‘What am I doing?’ ‘Why am I doing this?’ ‘Am I really an artist?’ I’d say that’s an ongoing issue.

Are you creatively satisfied?

I would probably say, not really. I just always feel like I’m struggling and I still work every day and we manage to make a living and get by. I feel like we never ever really made it big or anything, you know? So we still struggle. I guess if I ever got to the point that I didn’t feel that way then maybe I could say I was satisfied.

Lots of people have to give things up to pursue the things they love. Have you had to give anything up to pursue your art?

Certainly have. First thing that comes to mind is that for twenty years we lived in a big ol’ two-story house in the Munger Place Historic District in East Dallas. It was a great ol’ big craftsman house with a swimming pool in the back yard, the whole deal – and then the recession hit. We were making a living doing commission work. A lot of big hotel projects, restaurants and corporate office stuff. Things were great back then. And when that recession hit, that stuff dried up.

We struggled very hard, and we ended up having to sell our house. My wife misses that a lot. But we did have this 5000- square-foot place here in The Cedars and it wasn’t hard for us to turn part of that into a living space. So that was a tough transition.

I know it’s been hard on my wife, and she’s kind of come around. It’s been like five years. Back when we first moved here to The Cedars, it was pretty rough. But 15 years later, it’s changed a lot. There’s a lot more residential out here. It’s a lot safer. You can see people out here walking their dogs, jogging, riding bicycles and now there’s all this development with the Cedars Union and Four Corners Brewery, that Hotel Lorenzo, all the stuff happening on Lamar. And that’s bringing people. It’s making it safer. So you know, it’s turned out that this is an OK place to live.

But still we had to give up that cool old house.

My wife might answer that question in another way though. When we took off to graduate school in California – she had two kids when I met her – it was real hard to leave the kids in Texas. I mean, one was already in college and the other went to live with her dad, but we had to follow our path and do it. But we’re glad we’re all in Texas now, and we’ve got four grandkids and we’re blessed in that way. So I would like to say that it’s all been worth it.

You mentioned commissioned work. I wonder if there’s a difference between commercial work and non-commercial?

When you say “commercial,” the connotation can be misleading. When I bring up work with hotels, restaurants and stuff like that, I always felt like I was working with some really talented designers that I appreciated so much. They were artists in their own right at what they did, and I was fortunate to be part of their team and to be able to work with them. They gave me great opportunities to do amazing projects in different public spaces. I just saw that as a way to expand. I never saw it as “commercial.” I can say that it paid well.

I would love to be freed from having to worry about getting those good-paying jobs. I’d love to win the lottery and to be able to make anything I wanted and not even worry about if it sold or not. It would be so nice to just do what I wanted because I feel like I’ve put so much into building this studio.

I get this name, it was actually pinned on me actually, as this glass artist, and I would like to say, “Really, I’m an artist that works with glass.” I happen to have glass as the focus of my studio because I have this furnace and it’s burning gas, and you’ve got to make something to pay the bills. But I would love to be able to work in mixed media. I’ve done some sculptural work combining glass with different metals, stone, concrete, found objects and just stuff like that. I really do like working with other materials and not just glass. I’m not really what you might call a purist. There needs to be a reason to create with glass.

What makes you different and sets you apart from other artists?

I guess that I really don’t conscientiously try to be like other artists. So I don’t think that being like another artist is even an issue with me. I am what I am. And my work is what it is. And if it happens to look like somebody else’s work, well, who knows? Maybe I picked up a little influence here or there by seeing something.

But I think even when I did, it’s filtered through my creative process, so it’s going to come out looking like me.

Interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

COMMENTS