Welcome to the Art&Seek Artist Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the personal journey of a different North Texas creative. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will eventually paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists we’ve profiled.

Edyka Chilomé is a 26-year-old spoken word artist who’s trying to make her art full-time. She travels between Dallas and Washington D.C. – where her family lives. Jessica Diaz Hurtado reports for this Artist Spotlight that when Chilomé is challenged, poetry is how she fights back.

As a child – born Erica Granados-De La Rosa – Edyka Chilomé briefly lived in Lincoln, Nebraska. Her mother was a migrant farmer following the harvest. Edyka was in first grade when she wrote her first poem. Writing and reciting poetry was a way to prove herself to bullies.

“I was facing a lot of terrible racism at the school I was in,” she says. It was almost intentional, proving of my ability to speak English because they refused to believe that any of the brown children could speak English (laughs) But I loved it. it was very natural for me,” she says.

Chilomé is the daughter of Mexican and Salvadoran immigrants, both activists. Her mother focused on creating social change in church communities. Her dad was a human rights activist who escaped the Salvadoran Civil War. Like her parents, she became an activist. Much of her poetry explores her indigenous roots.

“Storytelling in the poetic form, in the Mexican tradition and other tribal tradition they call it flor y canto, the blossoming of a story reminds us that new life is necessary,” she says.

‘Flor y canto’ literally means ‘Flower and Song,’ but it also refers to spoken word poetry. This kind of storytelling helped her stay strong.

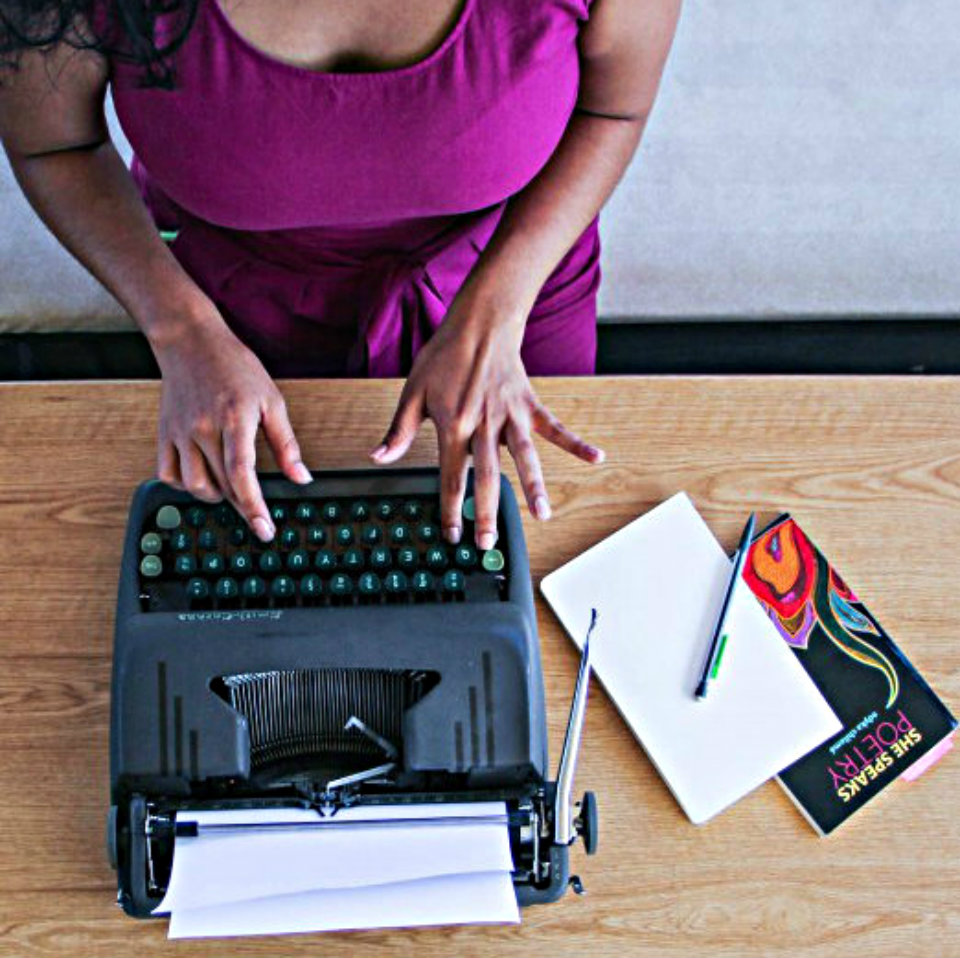

Edyka Chilomé. All photos: Jessica Diaz-Hurtado

“My journey into becoming a spoken word artist was really born from my need to heal myself,” Chilome says. “Activism can be a very draining place when you’re constantly fighting. It was the beginning of me coming home to myself,” she says.

At the Meet Shop in Oak Cliff, Chilomé flips through her self-published book, “She Speaks.” This is one of her favorite places to write. So it’s bittersweet to be here a few days before the literary center shuts down its day-to-day, open-door operations (it continues to be open for scheduled classes and events).

“Storytelling in the poetic form, in the Mexican tradition and other tribal tradition they call it flor y canto, the blossoming of a story reminds us that new life is necessary,” she says.

‘Flor y canto’ literally means ‘Flower and Song,’ but it also refers to spoken-word poetry. This kind of storytelling helped her stay strong.

“My journey into becoming a spoken word artist was really born from my need to heal myself,” Chilome says. “Activism can be a very draining place when you’re constantly fighting. It was the beginning of me coming home to myself.”

“My journey into becoming a spoken word artist was really born from my need to heal myself,” Chilome says. “Activism can be a very draining place when you’re constantly fighting. It was the beginning of me coming home to myself.”

Chilomé says she prefers to write with a typewriter – it makes her feel more connected with her poetry. She earned a bachelor’s in social and political philosophy from Loyola University in Chicago, then she moved to Dallas a few years ago to get her master’s degree in multicultural women’s studies at Texas Women’s University. And Meet Shop made her feel at home.

“I think that, especially for women and writers that are of color, we need a space that we can feel safe and speak our truths,” says Ofelia Faz Garza.

Garza is the founder of the Meet Shop, and also Chilomé’s mentor. She helped create the literary community that invited and guided Chilomé’s work. And she’s seen her grow.

“When I compare her to the pieces I’ve seen her now, she’s more creative and incorporating music and bringing in other artists.”

Chilomé now works as an artist full-time. She has performed her poetry and given speeches and lectures in spaces and to groups around the country, including the Dallas Museum of Art, Boston University, the Prindle Institute for Ethics at DePauw University and GLAAD. She performs poetry and teaches an online course at El Centro Community College.

She is both conflicted and inspired by Texas. “This is a state that is almost 50 percent brown, 50 percent mostly mestizo, gente indigena [indigenous people],” she says. “And we’re invisible. Invisible in the landscape of the city of Dallas and in North Texas. So there is an urgency for me to be a brown mestiza mujer [mixed-race woman] in this place, in this land to be visible, to tell the stories to recollect the stories to make sure that we’re educating our young people.”

Chilomé wants to give her writing a shot. But sometimes, she questions herself.

“Are my poems enough? Do I believe in this work enough?” she asks. “In the end of the day, it’s yes. Because it’s important for us.”

What have you had to give up to pursue your art?

My father wanted me to be a lawyer (laughs), my mother wanted me to get a Ph.D. to continue in academia. And I just wanted to live doing this work, creating these poems, creating these novels, creating these plays and supporting spaces where artists can be born. So I decided to become a working artist, which has taken a lot. It’s mostly a mental game of saying ‘I can forge my own path in this way and I can be creative enough to survive and make a living doing this with the support of people and with ancestral support.’

And things just come together, and you have money for rent, money for food every month and you don’t know how it’s working but it’s working. . . . But I’ve had to give up these notions that I’ll live monetarily well. And maybe I will one day.

So you’re about to write a piece and you have a blank page. What is going through your mind before you write?

Usually it’s like an alarm clock I’m learning to be disciplined to. If you’re hit with the words that are bubbling out, you have to put them down or they’ll go away. . . . So when I do sit down, it’s because I have this urgency, I have this itching. I have no idea what’s going to come out really.

Usually, the well-written poems, the intentional poems, the poems that are supposed to be birthed – I had no idea, I finished them and I look at them and am like ‘That wasn’t me, but I’m honored to be a channel for it.’

How has living in North Texas affected your work?

It’s been a really important experience to live in Tejas because unlike California, it feels like its been this land, and the people of this land feels like it’s been a victim of settler- colonialism and erasure, segregation. . . . These are things that are very real. . . . The lynching of Mexicans in Texas, the intentional sabotage of the Raza Unida Party. We’re still living this Wild West inheritance of the Indian needing to be controlled. This is a state that is almost 50 percent brown, 50 percent mostly mestizo, gente indigena.

And we’re invisible. Invisible in the landscape of the city of Dallas and in North Texas. So there is an urgency for me to be a brown mestiza mujer in this place, in this land to be visible, to tell the stories to recollect the stories to make sure that we’re educating our young people. To make sure that we’re upholding community spaces like the one we’re sitting in right now.

Your family is from Mexico and El Salvador. How has your family’s immigrant story impacted your spoken word /art?

My story being born to immigrant activists, people with intentional migrant stories, that they’re not afraid to live. All that gave me an orgullo, a pride of being a product of sobrevivencia, survival. Having inherited these skills of word and passion and dedication to our community and nuestros antepasados [our ancestors] in our stories. That fuels everything that I’ve done in my life.

COMMENTS