- KERA radio story:

Audio Player

- Expanded online story:

Filling the storefront window of the Webb Gallery are intricate replicas of windmills, the Eiffel Tower and a Ferris Wheel. The intricate structures, several as tall as three feet, were made by the late Dallasite, Venzl Zastoupil, and he made them from thousands — of toothpicks. Inside the Webb and up in the mezzanine gallery space is an exhibition of ghostly prints by the painter, Michel Nedjar.

And then — there’s the guillotine.

Not an original, French guillotine. This one’s an old contraption from a fraternal lodge. It was used to teach a new lodge member to trust his brothers – even when they got him to stick his neck out.

Julie Webb is co-owner of the Webb Gallery.

Julie Webb is co-owner of the Webb Gallery.

JULIE: “It’s a spring-loaded thing. It stops before it gets to your neck. But it’s really loud. [squeaky sounds of pulling up the blade] All right.” [Loud crash followed by laughter.]

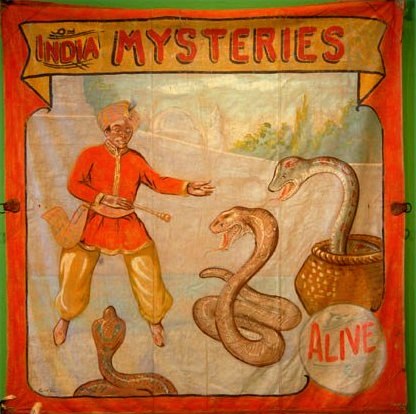

The Webb Gallery specializes in this kind of thing, the funky and the visionary: folk art, outsider art, backwoods Americana, art from self-taught painters and prophets. As collectors, Bruce Webb says that he and his wife Julie are “flea-market trained.” The two native Texans enjoy driving cross-country to scout for things like hand-painted carnival banners from the 1940s, banners hawking freakshow acts like the man with “Two Noses” or “Creation: The World’s Most Amazing Attraction (Children Under 16 Not Admitted).” The Webbs have been doing this for 25 years.

BRUCE: “Getting started in this, no one really wanted the weird stuff back then. So we kind of focused on the unwanted and the forgotten, the things we like the best.”

“Lodge art” has been a major interest of theirs. Currently, the Webb Gallery is displaying more than 150 artifacts from secret societies, such as the Masons, the Elks and the Odd Fellows. The items include old parade banners, theatrical costumes, posters and amateur props. For the past century or so, many fraternal artifacts could be ordered from “regalia” catalogs (they still can online). But the Webbs are more interested in those rural lodges that couldn’t afford the standard, professional accessories — and made their own.

Aimee Newell is the director of collections for the National Heritage Museum in Massachusetts. The museum was established by Scottish Rite Masons. Its focus is American history – with an emphasis on the Masons. Newell says there’s a market for “fraternal collectibles.”

NEWELL: “I think that there’s been a lot of interest in popular culture in fraternalism and that’s drawn attention. And people have naturally found it intriguing.”

By “popular culture” Newell means movies likeNational Treasure and From Hell, movies that have sensationalized the Masons as a clandestine, even murderous, force. And she means The Lost Symbol by Dan Brown, author of The Da Vinci Code. Released last week, the thriller features the Masons in yet another sinister conspiracy.

By “popular culture” Newell means movies likeNational Treasure and From Hell, movies that have sensationalized the Masons as a clandestine, even murderous, force. And she means The Lost Symbol by Dan Brown, author of The Da Vinci Code. Released last week, the thriller features the Masons in yet another sinister conspiracy.

That’s not exactly what interested Bruce Webb. Yes, the secrecy was intriguing. But it was the layers of symbolism and meaning that appealed to him.

BRUCE: “I started to get interested in mysticism and collecting books on the Rosicrucians and the Masons – things that are a little spooky. But the more you get into that kind of thing, the more you realize there’s not a whole lot to be spooked about at all.”

There’s another attraction. Webb likes forgotten things, faded traditions. And America’s history of fraternal organizations qualifies as one.

BRUCE: “To me, nothing is quite as fascinating as going into old lodge halls and seeing what kind of treasures might still be there.”

[sound of footsteps]

Julie Webb takes Dexter, the couple’s Boston terrier, out for a walk.

Julie Webb takes Dexter, the couple’s Boston terrier, out for a walk.

JULIE: “C’m’ere, Dexter. Let’s go.” [Door closes.]

The Webb Gallery has been the couple’s home for 10 years. The three-story, cast-iron-front building was put up just off the courthouse square in Waxahachie in 1902. Around that same time, membership in fraternal orders in America reached almost 40 percent of the adult male population. Needless to say, membership has declined considerably since then.

But Waxahachie is like many of the rural communities that the Webbs explore. A lodge was often one of the first buildings to go up in town — a sign of its importance. In fact, when you stand on the square in Waxahachie, just down the street from the Webb Gallery, you can see what once was the Masonic hall — and there’s the Elks hall, the Knights of Pythias hall and what still is the Odd Fellows lodge.

Sometimes, American history is buried in plain sight. Or it’s on display – in a funky art gallery.

0 Comments