Welcome to the Art&Seek Artist Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the personal journey of a different North Texas creative. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will eventually paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists we’ve profiled.

Video: Dane Walters

For the past few weeks, houses have been popping up all over Oak Cliff. These aren’t the luxury apartment complexes you might’ve seen in Bishop Arts, though. In fact, you won’t even see construction crews working on these houses because they pop up so fast. They’re artist Giovanni Valderas’ way of responding to Oak Cliff’s gentrification.

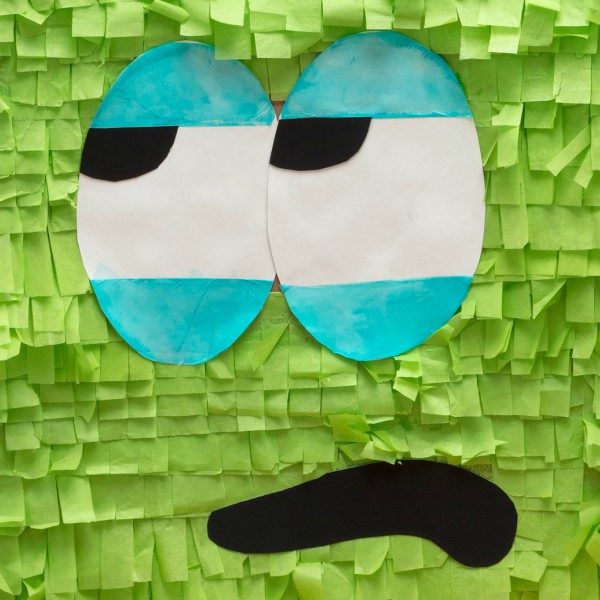

On a cold morning in South Dallas, and Valderas’ home studio is filled with the sound of decorative tissue paper being shuffled. It’s a holiday and most of his neighbors are still bundled up in their beds. Valderas, a gallerist at Kirk Hopper Find Art and an adjunct professor at Mountain View College, still has sleep in his eyes as he sorts the neon-colored tissue paper he’s about to start gluing on to a cardboard structure that’s shaped like a house.

“So when I start to assemble these, I try to have my tissue paper cut in advance,” he says. “And I like to begin with the feet – the ‘patas,’ as my mom would say.”

Valderas is creating a sculpture of sorts: It’s a piñata.

“I try to use colors that are associated with the neighborhood I live in and that I grew up in,” Valderas says. “So these bright oranges and bright greens I think symbolize my community, but also symbolize hope.”

The house-like structure is about to be covered in glue and paper. It’ll also be made to look human. It’ll even sport a sad face. The expression? Imagine a depressed-looking “Thomas the Tank Engine.”

“What I like about the piñata is that there’s this kind of subversiveness to it, right? In the beginning, he’s really fun and festive. Then, you look at it and then you start to get that there’s something more to it.”

He calls the pieces “Casita Tristes,” which translates to “little, sad houses.” They’re his response to the wildfire gentrification of Oak Cliff. Big, new housing developments go up and — boom — Valderas places his little, sad paper houses right in front of them.

Art&Seek reached out to the Dallas Police Department to make sure that Valderas isn’t breaking any laws with his project. And Senior Corporal DeMarquis Black says he looks at the houses as a type of protest, which isn’t illegal.

“So long as he’s not blocking walking paths on sidewalks or impeding traffic on the streets,” Black explains, “then I wouldn’t see a reason for DPD to ticket the artist.”

“I’ve seen people stare at them. And at first, it’s like they don’t know what’s going on. I’ve even seen a woman — she was white and looked a little well off — have her son stand next to them for a photo,” Valderas says. “But once she started to take the photo, she stopped. She saw the construction behind her son and the house, and I think she finally understood it all.”

Valderas is part Guatemalan, part Mexican-American. He lives in an area of Oak Cliff that’s mostly Latino. And many of his neighbors are in danger of being priced out of the area. He says they feel overlooked.

“I think one of the most valuable things about Giovanni’s work,” Janeil Engelstad says, “is he’s creating a public voice for a larger community.”

Engelstad is an artist and an activist. She runs an organization called Make Art with Purpose. They use art to advance social causes. And she thinks Valderas’ little houses could have a big impact.

“There is great potential and value for Giovanni’s project to grow out of Oak Cliff because this is not a small neighborhood problem. This is a national problem,” Engelstad says.

Sandy Rollins, the executive director of the Texas Tenants Union, agrees.

Rollins works to help low-income people find better living conditions and stay in their homes. She says more people people are finding that hard to do.

“We’ve worked with a lot of people who have been displaced,” she says. “We’ve seen it happen in Oak Lawn. We’ve seen it happen in Northeast Dallas. It’s happening right now in Vickery Meadow.”

Rollins says the new construction is one reason land values — and rents — are going up. That makes it harder to stay in the neighborhood. The Economic Policy Institute estimates if you make minimum wage ($7.25 an hour ), your entire paycheck would barely cover a year’s rent at an average Dallas apartment. You’d have nothing for utilities, food, transportation or clothing.

“There is not enough affordable housing in this city, and I think people are angry at the city’s role in displacing longtime residents,” Rollins says.

“For me, it’s scary,” Valderas says. “It’s hard to know that there is this kind of cultural and community erasure that’s happening. You know like, ‘We want to capitalize on your culture, but you can’t be here at the same time.”’

Valderas hopes that the “Casita Tristes” spark conversation about affordable housing and the gentrification of communities, specifically in Oak Cliff. He wants people to reach out to the Dallas City Council and to demand more funding go toward helping low-income individuals.

Valderas says he doesn’t want growth to stall in his community, he just wants it to be organic. He says Latinos invested in Oak Cliff by opening paleterias, bakeries and mechanic shops. Those businesses made the area attractive. He doesn’t want them to go away.

“I think this is a really important moment that we’re in,” Valderas tells me. “I think a lot of individuals have taken notice of what’s happening and I think these “Casita Tristes” – these sad, little houses – it can spark that conversation.”

Judging from social media, the conversation has started. People are posting photos and sharing the message. Some have even taken the sad, little houses and placed them on their porch as a sign of solidarity.

Though, Valderas says his casitas are moving faster than he can put them out.

How does being here (in North Texas) affect the production of your art?

Living in my community allows me to be responsive in my art practice. Having grown up in the Oak Cliff area of Dallas, it was easy to be influenced by the cultural aesthetics of my neighborhood, which translates to the work I’m doing today. My community has given me many lessons in history, humility and appreciation.

As for the arts community in Dallas, it’s great to have so many visual artists, performance artists and poets in the Metroplex. I believe they all serve to inspire and encourage us to grow as a community.

Have you been able to quit your day job to pursue your art?

In an ideal world, quitting my job would be fantastic, but in reality, it’s difficult.

Like most artists, I have responsibilities that must be met, children to care for, bills to pay and traffic to sit in. I will say, the second best thing next to being a full-time artist is having a job in the creative sector with a boss (Kirk Hopper) who is flexible with my schedule. For that, I’m grateful.

You have children. You’re an artist. And you have a million things happening all the time. How do you balance your life?

Being a father, advocate, board member for EASL, assistant gallery director and artist is very difficult to balance at times. But, I have found it beneficial to have a disciplined schedule with plenty of to-do lists.

Are you creatively satisfied?

Most of the time, I am not. As an artist, I’m constantly trying to think of new ideas or how I can improve on my creative talents.

What makes you different or special compared to other local artists?

I don’t consider myself “special” in any regard. However, I do consider myself passionate in my artistic endeavors and in local politics. Currently, I’m thinking about ways of engaging the general public more and using art to be a catalyst for change when it comes to important issues.

Are there other artists doing what you do? If so, what sets you apart?

I think it’s difficult to claim ownership of any one medium. There are few artists that I’m aware of that are doing great things when it comes to transcending the craft of the piñata; fellow Guatemalan Justin Favela from Las Vegas and Josue Ramirez from South Texas are a few.

What inspires you?

I’m inspired when I see a really great show. I’m also inspired when I’m having a really great discussion with friends and colleagues.

Why did you make this sort of artwork?

Teaching art appreciation at Mountain View College, I realized contemporary artwork can be intimidating to some.

If I wanted my work to resonate with my community, I knew I had to use the visual language we are comfortable with.

If I wanted to engage my Latinx community, I also knew I would have to come to them, hence the site-specific and guerrilla installations. My work appropriates elements of the piñata in an effort to utilize the piñata as a vehicle to create awareness, reflection and empowerment.

Interview questions and answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

COMMENTS