Welcome to the Art&Seek Artist Spotlight. Every Thursday, here and on KERA FM, we’ll explore the personal journey of a different North Texas creative. As it grows, this site, artandseek.org/spotlight, will eventually paint a collective portrait of our artistic community. Check out all the artists we’ve profiled.

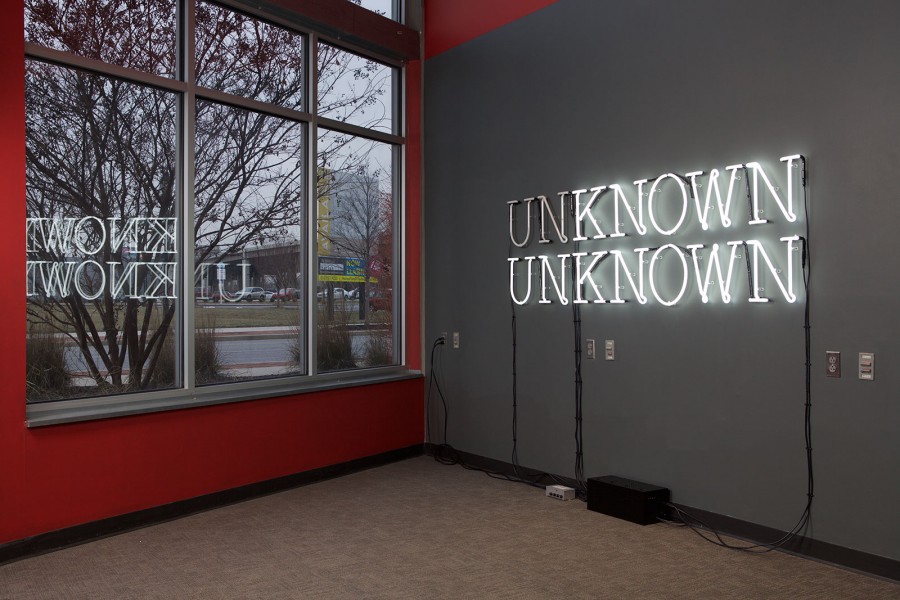

“You are (on) an island” Photo: Mike Fleming

Alicia Eggert isn’t a writer, but she likes to play with words. In this week’s Artist Spotlight, the Denton sculptor explains how her work uncovers layers of meaning in common phrases and places.

Alicia Eggert doesn’t make traditional sculpture.

“I make a lot of art that looks like signs,” said Eggert. “I play with words as if they were found objects.”

For example, in 2013 she created a wall-sized neon sign (view above) that reads “You are on an island,” but when it blinks it reads, “You are an island.”

“Single words can also have many definitions,” Eggert proclaimed at a 2013 Ted Talk. “They also have the ability to possess great depth and complexity. One word can be both simple and profound.”

Eggert moved to North Texas in 2015 to teach Studio Art and the Sculpture at the University of North Texas in Denton. Her artwork and installations are already garnering attention in the region.

Last fall, she built three marquees inside the AT&T Performing Arts Center (view in slideshow above). Each sign spelled the word “future” in one of the world’s three most common languages – English, Chinese and Hindi.

The signs used 206 light bulbs to represent the world’s 206 sovereign states. The lights flickered on and off to depict each state’s standing on human rights issues, like gay marriage and the death penalty.

“I think about the words that I’m using and I try to come to a completely new understanding of them. I try to give them a physical form that can change over time,” said Eggert.

Eggert studied to be a designer, and initially worked at an architecture firm. But a sculpture class she took as an undergrad kept calling her. She quit her job and pursued her masters in fine art.

“It was very much a decision that I had to make as opposed to this innate kind of talent that I had inside of me my whole life.” Eggert said.

Eggert’s father was a Pentecostal minister. Growing up she went to church several times a week. At services, she often saw people speaking in tongues. Today, she’s an atheist. Yet spirituality still affects her work as she struggles to grapple with ideas of existence and mortality.

“I wonder how everything fits together,” Eggert said. “And – you know – I’m just trying to understand how the world is going to go on without me when I die. Cause I think as humans that’s something that we all have to confront at some point.”

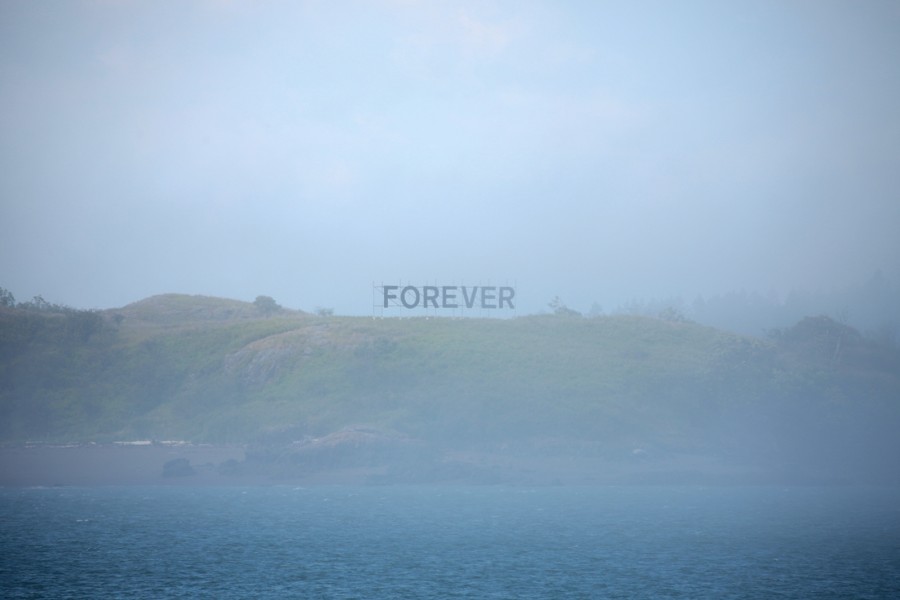

She explores these questions in a show called “Partial Visibility” (view photos from show below). It’s on view at The MAC in Dallas. One piece is a video called “On a Clear Day You Can See Forever.”

“I had a teaching position in Maine and literally lived a five minute walk from a beautiful place in Portland called the Eastern Promenade, which had amazing views of the bay and islands and all of that. So it became an everyday experience for me to see that view and also to experience the changing weather conditions that that coastal area experiences.”

“The video itself is of a large scale temporary sculpture public sculpture that says ‘Forever’ that I put in the landscape and I filmed appearing and disappearing in the heavy fog that blankets that landscape.”

“It’s an amazing place in the world where the tide comes in and goes out every day, so really dramatic tidal changes and really really dramatic fog. And you could see the fog rolling in across the water and it was kind of like this white wall. On a clear day you have this beautiful view and you really feel like your sense of place in the world. On a really foggy day you feel like you’re could almost be anywhere.”

“So that was one of the things I wanted to capture with this video. Part of my concept is that we’re at this unique place right now as a society, but also a human race, in that we’re fully understanding the temporary nature of our world and our existence.”

“The way we experience time as humans is very finite and linear, but we exist in this world that is cyclical.”

The 60 mph winds that accompanied the storms at the end of March tipped Eggert’s “Forever” installation over. Here she is repairing it with the aide of students and volunteers. Photos: Hady Mawajdeh

When did you begin to call yourself an artist?

I had a lot of trouble calling myself an artist for a long time, because I came to art sort of late in my college career. I was in my early 20s when I decided that art was something that I wanted to do. It was very much a decision, too. As opposed to this innate thing or talent that I had inside of me my whole life. There are a lot of artist that say things like ‘I’ve been drawing ever since I could pick up a pencil.’ That was never me, so I really questioned whether I was really an artist. I questioned my creativity. I think that in our society we put artists on pedestals a lot, so it took me a long time that it was a decision I could make. Now I know it’s something that I can practice and I can kind of hone my skills and my abilities over time. I didn’t need to have some genius that was already living inside of me.

You’re not from North Texas, but this is where you work, so I want to know how North Texas and location affect your art?

When I think about Texas I think about – man I don’t even know… I’ve lived in Texas for about two years. Before Texas, I lived in Maine for four years and the landscape there really influenced my work in a lot of ways. Now that I am in Texas the landscape is very different. It’s much more flat, wide open, there’s big sky but there are a lot more billboards here than there are in Maine. I think billboards are illegal in Maine. I guess they’re trying to preserve some sort of landscape. But there are so many here in Texas and I think that they are having an influence on me. I really want to put my work on a billboard. I’ve never had the opportunity to do that before.

Photo: Mike Fleming

Are you creatively satisfied?

I get so much satisfaction out of being a creative person – yes. I am really lucky to have the job I have as an arts professor. I enjoy working with students, because it keeps me on my toes and really aware of what going on in the younger creative minds. It also allows me a lot of time to work on my own projects as well. So yea, I feel really creatively enthusiastic and excited and optimistic. (laughs)

Have you had to sacrifice anything to pursue your career in art?

I’ve had to let go of a sense of control. I think that as a conceptual artist I ideate first, I conceptualize the idea, then I choose the ideal material and situation for that idea to come to life and ultimately, I think that a project is most successful when there are things that happen that I could have never have anticipated.

What makes you different or special from other artist working in your medium?

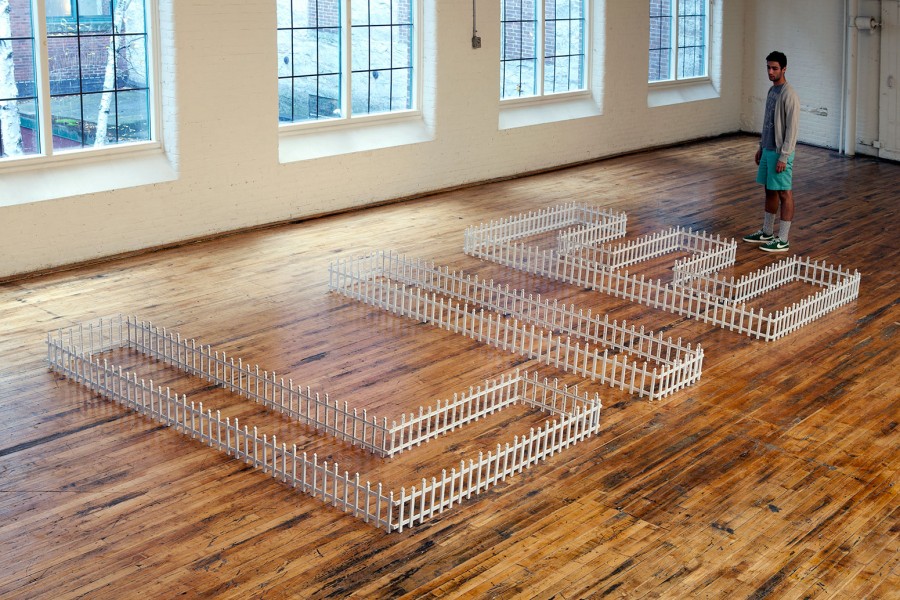

Oh man. (laughs) I think what makes my work different from other language-based artists is that I really approach words as if they are objects. The same way that I would approach a found chair. If I wanted to make that chair into a sculpture, I would need to completely disassemble it, maybe add somethings to it and then reassemble it into something new. When I make my work I think about the words that I’m using and I try to come to a completely new understanding of them. I try to give them a physical form that can change over time.

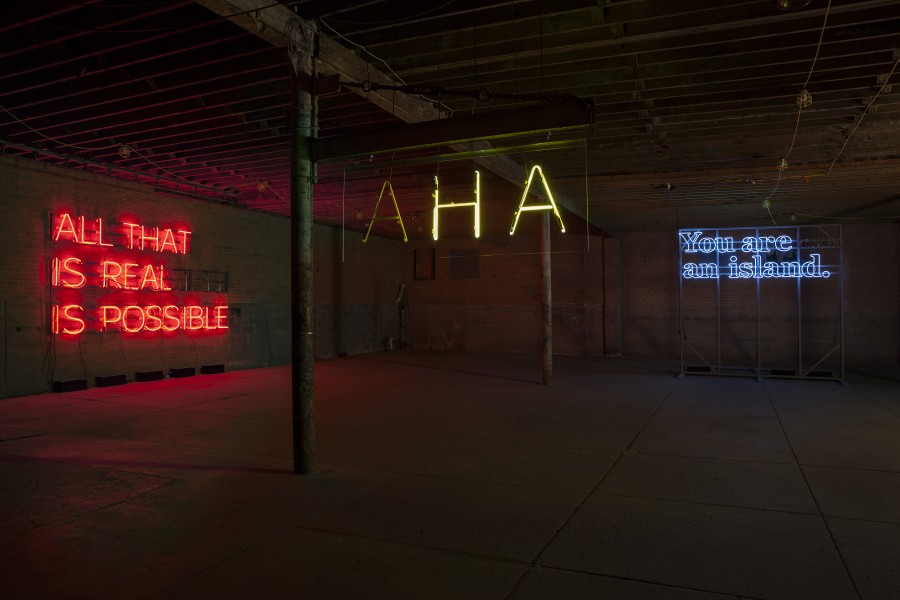

“All That is Possible is Real” Photo: Mike Fleming

Can you take a moment and look back at your life and tell me about something that lead you to where you are today?

When I was a kid I used to write fictional stories a lot. That was my medium of choice. When I was younger I would sit at my mother’s typewrite and type up a story. I was kind of imagining a whole other world that would go along with the story.

I was also very interested in the environment and architectural space. The way those things were organized. So I can totally see the ways those things fit into what I am doing today as an artist.

What sort of stories were you writing? Can you recall any of the tales?

(laughs) No. I remember I used to love drawing maps and doing treasure hunts. And I would make up stories that went along with those treasure hunts. I would bury things in my yard and then do everything in my power to try and forget where those things were. (laughs) That was something I used to do a lot. I also used to try and get lost. A lot. I was trying to make my surroundings, which felt very familiar, feel very unfamiliar in some way.

“AHA” Photo: Mike Fleming

You mentioned your mother’s typewriter. Did your parents have any sort of creative influence on you or were you the artistic black sheep of the family?

I am the black sheep (laughs). My father was a Pentecostal minister for most of my life. And my parents were actually missionaries. When I was a kid, we lived in Cape Town, South Africa for four years – during the final years of apartheid. Anyway, they would say that they have no creative juices in them whatsoever. But I think that that’s not really true, because a lot of the nature of preaching is coming up with stories, entertaining people and creating metaphors for different things. You know I grew up going to church many, many, many times per week. And my mom doesn’t give herself enough credit, but I think she’s a very creative person and she would always make the coolest birthday cards and Halloween costumes and things like that.

But ultimately I think the way that my upbringing has influenced me as an artist is the spirituality aspect that I think comes through in my work, because I am always grappling with ideas around time, mortality and existence. A lot of my work deals with existential questions or problems. But although I am not a religious person today – I am an atheist – I do wonder how everything fits together. I am trying to figure out how the world is going to go on without me when I die, because as humans, I think that’s something we all have to confront as we go on.

Interview questions and answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.

0 Comments